Author: Nathan Cohen

Published: Cohen, Nathan. ‘De Pictura: Journeys Through Painting.’ OAR: The Oxford Artistic and Practice Based Research Platform Issue 2 (2017), http://www.oarplatform.com/de-pictura-journeys-painting/

The search for understanding validates and gives purpose to our existence. It defines who we are and what we may become. It is a source of invention and enables us to find expression in many and varied forms of creative and intellectual endeavour leaving traces of our journeys for others to learn from and enjoy.

The following are a collection of thoughts on some of the paintings that I have been inspired by as an artist. All of the paintings I refer to can be seen by visiting the National Gallery in London, a place I have been to many times in search of inspiration and reflection and a home to many more paintings that offer all who take the time to visit the enjoyment of the experience of looking.

Each artwork captures a moment in time and speaks of humanity through the intimacy of their subject matter and form - a validation of the human spirit in a dynamic world of change. When encountering the reality of these paintings their existence as tangible forms are defined and reshaped in the imagination and the memory of them.

--------------------------------------------------------

In considering the question of what makes painting a valid means of expression I am reminded of those images I return to for inspiration as I seek to create my own pictures.

There is a space that we know of that we can imagine and that also exists but we can never see. It resides within each of us and yet we need to apply our mind to comprehend it and is a constant as we navigate our journey through the world around us.

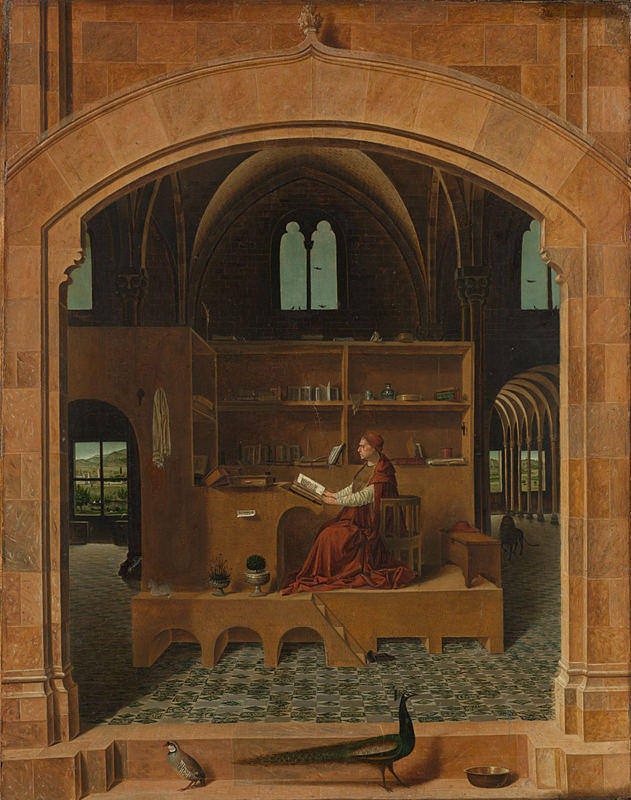

Figure 1: St Jerome in his Study (c.1475) ANTONELLO da Messina (National Gallery London)

In Antonello da Messina’s painting St. Jerome sits contemplating a text he is reading set within a mind like architecture. We look in but always from the outside. His space is within. In searching this small painting our eyes can wander as the lion does through corridors that recede into different perspectives of the window framed landscapes beyond, as if we look through the eyes of the building. Above birds alight silhouetted by the blue of the sky, their movements of flight and repose caught as saccade like moments in time.

The keys hang silently from a nail behind him supported by a structure that is encapsulated by the architecture that surrounds it. And elsewhere within the space objects, animals and birds reside. The painting is replete with metaphorical references and the more you look the more you find. There is a hidden geometry that places each form within its given space enabling the narrative to unfold. Of necessity this is a painting that invites interpretation, for without curiosity there would be no questioning, and without questioning there would be no intellectual pursuit.

While we live now in a different age, and the historical and cultural context that informed the creation of this artwork may have changed, it still speaks of ideas that we relate to today. The painting invites us to wonder and to reflect and it rewards our patience in contemplating what we see by discovering new dimensions within its intimate form.

---------------------------------------------------------

Figure 2: The Arnolfini Portrait (1434) Jan van EYCK (National Gallery London)

Figure 3: The Arnolfini Portrait - detail of mirror and rosary (1434)

The more I see the more I question what I am looking at and what relevance this may hold for others. Artists have explored different practical means to both comprehend and extend their means of observation including optical, mechanical and graphic instruments and the use of mathematics, geometry and proportion to construct their images.

Both the lens and the mirror refract and reflect light, as does a painting whose construction may consist of layers of colour upon a reflective background. The couple in the Arnolfini Portrait (1434) hold hands before the painter Jan van Eyck, and his reflection is to be found in the illusion of the mirror behind them.

This plays with our understanding of where the paintings surface resides for while we know this to be an illusion yet we can be convinced by the seeming reality of its construction. Physicists and neuroscientists have come to appreciate the profound nature of the complexities that lay at the heart of our existence and our ability to understand it, whether contemplating a multi-dimensional universe or comprehending the way our brain interprets what we observe.

Paradox lies at the heart of painting and artists find ways to depict spatial forms that challenge interpretation. Painting is essentially abstract, whether seeking to represent a likeness of things seen or imagined and we can be intrigued by the play with spatial expectation to be found in many works of art that explore the encounter between the second and third dimensions.

In questioning what we see we also reaffirm our comprehension of the reality of the space we exist within. We sense we are looking at an illusion and where this meets the reality of our physical world we can derive pleasure from the experience, a reward for our intellectual engagement in seeking to ‘resolve’ this intriguing spatial conundrum.

-------------------------------------------------------

Figure 4:A Young Woman standing at a Virginal (about 1670-2) Johannes VERMEER (National Gallery London)

Light filters through the window illuminating a room and its contents. References to a world outside can be seen in the landscape painted on the instrument lid that mirrors the window at the left of the painting, and in the picture that hangs high on the wall behind, a reminder that this interior is part of a larger world. A chair awaits and she looks toward you, her hands resting on the keyboard of the virginal.

In contrast to our witnessing of St. Jerome we are invited to be a part of this scene and the painting's composition suggests we are present as a participant. The three-dimensional properties of the space are depicted in the geometries of this painting, a dialogue between the architecture and furniture and the viewer and the viewed. This a moment of encounter and we are welcomed into the painting both by its subject and its construction.

Where there is detail so there is also questioning of what we really see, the surfaces dissolving into flecks and dots of colour as you approach to inspect more closely. This is most clear in the depiction of the human form, the face and hands appearing almost out of focus in comparison with the other surfaces in the painting, as if in an early photograph where movement blurs the image during a long exposure.

The question of where to locate focus is significant in the composition of an image, for in the choice the painter articulates intention. There may be one or many foci and they offer a means to comprehend what is depicted and how the space within the painting can be interpreted.

The viewer brings their own perspective, both literally and in terms of experience. We project our own thoughts upon what we see in a painting and seek to compare and relate the visual sensation to memories of other things seen and felt. This is a multi-layered process which can stimulate associations across time and place, the painting providing a catalyst for the imagination.

--------------------------------------------------------

Figure 5: Doge Leonardo Loredan (1501-2) Giovanni BELLINI (National Gallery London)

The Doge Loredan has gazed serenely from the painting by Giovanni Bellini for centuries, a picture of calm repose reflecting all of the painters' skill in the creation of a work of art that appears timeless and yet of the moment. There is both a distance and an intimacy in the form of this image, with a human scale that invites closer inspection.

He sits within an atmospheric blue that appears to modulate his figure with an embracing subtlety, complementing and encompassing, and suggesting a depth of space within the picture's surface. It is a depiction of light and its ability to pervade our space, a medium without which the painter's art could not exist and we could not see. It is a surface that is simultaneously ethereal and tangible.

Mask like, the Doge looks beyond the viewer and the impression is of a reflective man of experience. The sculptural quality of the picture's construction both dignifies and renders emblematic the role of the sitter. Yet while it may have been commissioned to validate the role of public office being celebrated, the sitter's humanity is presented in a way that all can comprehend and relate to.

Upon the stone base an illusory piece of paper is painted with the author's name inscribed, a mark of his achievement and an indication that he is deemed worthy of patronage to create this artwork at this time.

----------------------------------------------------------

Figure 6:Self Portrait at the Age of 63 (1669) REMBRANDT van Rijn (National Gallery London)

In contrast to the Doge the sitter's eyes meet our own in Rembrandt’s self portrait of 1669, the year of his death. In this painting the calling card left by Bellini is replaced with a direct encounter with the artist himself. Except he would have been examining his reflection in a mirror to make this painting and we are seeing him as he would be seen by himself.

The light that pervades the canvas suggests an internal space, the shadows capturing the luminosity that bathes the head of the artist rendering the rest of his form as if slipping quietly into the embrace of an encroaching darkness. The intense blackness of the eyes invites contemplation of the space within, a space of which we all may be aware but must spend our lives to comprehend, a moment of self awareness and doubt.

The artist as subject offers insight into the creators’ mind but also presents us with the challenge of truly comprehending what we see. At one level it is a picture of another person, and yet the intimacy invited by the immediacy of contact invites a more personal emotional response. We begin to wonder what it is that he sees as he looks upon himself, what he wishes to impart by creating this painting. Rembrandt painted several self-portraits over his lifetime and we can see his progression from a young man enjoying the success of recognition to his later paintings that reveal the experiences of a life lived and coming to its end. We can make this journey with him through time and the portraits also speak to us across the centuries of our own mortality and experience.

For an artist there is always the next painting to be painted that continues the journey and there is the sense there is never enough time, but in the act of pushing the boulder each time to the top of the mountain there are the moments of completion that validate the effort made. In this painting we are offered a rare moment of communion with one who has lived that experience and who, still now, can share this with us as we live ours.

-----------------------------------------------------------

© Nathan Cohen 2017 (Text)

All images © 2017 National Gallery London and are reproduced here under Creative Commons Licence (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0): http://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/image-download-terms-of-use?img=n-1418-00-000032-wz-pyr.tif&invno=NG1418