Nathan Cohen†

Fig.1 - Monument Valley

In questioning what we see we must inevitably have recourse to our experience of the physical world around us. The pictorial offers us a way to explore these experiences and reinvent the world we see. While the picture plane may be viewed as a window onto an illusion of space, it is also the surface upon which spatial reality may be rebuilt.

Our ‘picture windows’ are not confined to the flat of the wall or the canvas but may be seen in artefacts from around the world. The humble pot has been elevated to an art form by many cultures over the millennia and embraces the notion of the utilitarian finding form within the imagination to become a means of expression.

Fig.2 - 'Planet' Acoma Seed Bowl

The hand of the potter may leave its trace or be wiped clean, a slip replacing the bare clay, providing the ground for an image. The brush is dipped into the paint and a trace for the form begins; perhaps a geometric motif, recalling in abstracted form the essence of rain clouds or mountains, or images evocative of natural forms; a bird, a fish or a flower. The painters’ ground is not the flat of a canvas but the round of a globe, with an exterior which reveals itself as the pot is handled and carried. (1)

Abstraction may be viewed as a transformative process whereby forms are conceived that convey and articulate ideas. For some artists the initial inspiration may be observed forms, experiences or places, and for others the enquiry may begin with exploring formal relationships between artificially conceived spatial and structural elements, which are not intended to be a likeness of other forms, or a combination of these approaches. There may be a desire to express ideas that speak of experience of interaction and exploration of how our perception enables and challenges us in this endeavour. (2)

Fig.3 - 'Three Rivers' Petroglyph Site New Mexico

There is a long legacy of abstract imagery in the pictographs, paintings, pottery, weaving and artefacts to be found globally which continue to be profound sources of influence for artists today. These include many types of pattern including spiral, maze, grid, linear, diagonal and concentric forms arranged in varying combinations of complexity.

Fig.4 - 'Cactus' Kew Gardens

Our fascination with symmetry and asymmetry is evident in the forms and structures we create and informs compositional choices applied to all aspects of manufacture. We find in natural forms evidence of ordering principles that excite our curiosity and we have developed a deeper understanding of structure inventing the Golden ratio, perspective, tessellation, Fibonacci sequence, impossible figures, nonlinear dynamics, n-dimensional and fractal geometries, to name a few. (3)

We may discover some of these forms and spatial constructions as we contemplate how to evolve our artwork. In doing so we encounter a rich tapestry of formal elements and ways to articulate them with which we can further our invention and better understand the forms and images we wish to create with intuition playing an important role in this process. (4)

This is an evolving process and one which can offer insight into how we perceive space. When Brunelleschi stepped back into the door whose frame outlined the view of the building he wished to represent, the fixing of the edge of the observable space defined it as a picture plane onto the three-dimensional space beyond, marking a moment where the framing element established a means to create a spatially measurable illusion of reality. However, it also defined a boundary between the real world of the viewer and that of the image and ensures our perception of what is depicted pictorially remains consciously an illusion.

We may take this invention for granted today and are familiar with looking at artworks that represent to us a likeness of the world we are familiar with in a way that is spatially convincing, allowing us to engage with the illusion of space as an extension of our real world reality.

So why would being concerned with the way an image is presented be significant and how might considering this question help us to better understand visual perception and advance pictorial invention?

Fig.6 - Kodaiji Temple Kyoto: view of gardens at night from within temple

The creation of an illusion of space that can be interacted with on a human scale can be seen where the properties of art, architecture and effects of light combine. Historical examples of how we invent pictorially to create the illusion of reality with light, surface and material in an immersive way are visible in Japanese fusumaē (screen paintings), Neo-Assyrian wall reliefs, Roman mosaics and Renaissance frescoes, to name a few.

Fig.7 - fusumaē Kyoto Temple interior

How we encounter the world is essentially a very personal act and we do this in a way that is both knowing (based on prior experience) and questioning (open to new experience). In choosing to make an artwork I am seeking to explore both of these perspectives and in doing so one of the big challenges is how to make an illusion of space appear real and to find a way to make spatially comprehendible what is in essence an invention. Over the years I have been exploring visual perception evolving a way of working that embraces a range of technologies, methods and media to create forms that engage with different aspects of questioning what we see.

Fig.8 - 'In Sight' Nathan Cohen 2005 Pigment and Casein on Cut Panel

To achieve this it is possible to be creative with spatial arrangement in an artwork that, while clearly defined, is also open to interpretation resulting in illusions of space that are intriguing for the viewer, enhance engagement and challenge spatial perception. Illusion of depth may be perceived as being more than one plane sitting in front of or behind another. It may also be conceived of in such a way that a surface may appear to recede or advance in one area, but change its spatial position in another.

Fig.9 - 'Saccade Image 3' Reiko Kubota 2007 NTT Laboratories Japan

Abstraction can be applied to construct images as a starting point for inventing pictorially and spatially. If the elements that compose the image define its boundaries, rather than sit within a predetermined frame, an alternative dynamic in its relationship to the space within which it exists is created. Locating the artwork directly within its environment using the architecture as its support can render its form architectonic, and utilizing space to construct an artwork in the round produces an architectural form integrating the observer within it. Kinetic, optical, light and digitally interactive elements can also be explored in the creation of art forms that offer an immersive sensory experience, including lens based technologies that can be used creatively in constructing artworks which seek to question perception and enhance understanding of what is seen.

There is now considerable interest within the neuroscience community in researching how the brain works when perceiving visual stimuli (5). Visual forms that play with spatial ambiguity may offer insights into the way the brain functions, but artists have known for a long time that we are intrigued by images that appear spatially irresolvable and I am interested in extending this in ways that also play with our preconceptions of how imagery is presented.

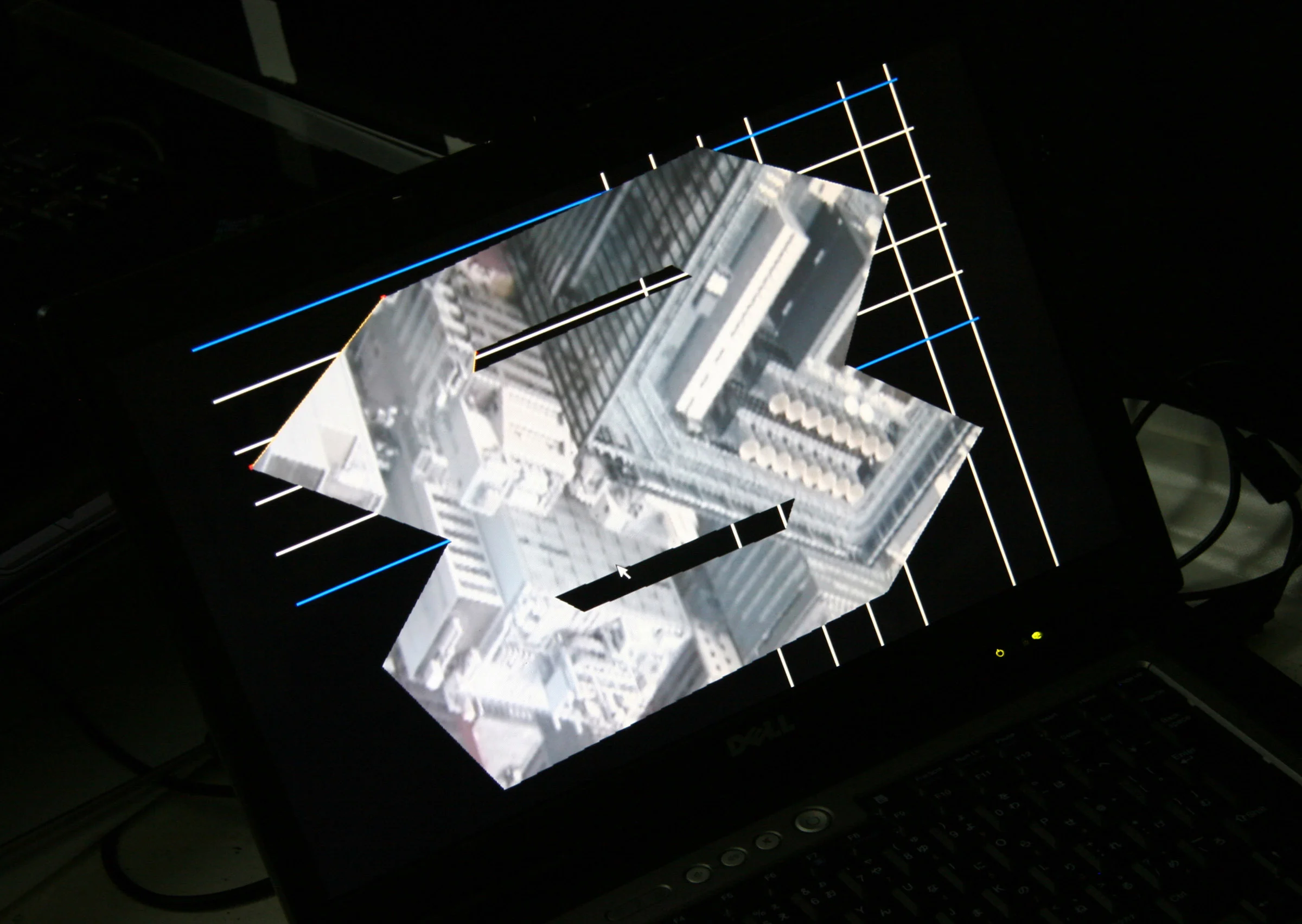

Fig.10 - 'Intangible Spaces' Tokyo 2010 Nathan Cohen - computer display image for projection programmed by Tachi Lab

The computer has in its modern form transformed the way we disseminate ideas, interact with one another and enhanced our capacity to acquire information. From the artist’s perspective digital imaging presents opportunities for visual invention and challenges in how visual form is mediated. In my artwork I use the computer as a means to create imagery that would not be possible without its use, and that enables exploration of an artificially created space that enhances spatial awareness and challenges our perception of what we encounter. The computer enables the use of real time and recorded moving and still images to be embedded within artwork previously limited to still imagery, and makes possible the fragmentation and reconstruction of the picture plane into multiple moving images with a remarkably high degree of resolution.

There is a different sensibility to image generation on a computer compared with the articulation of visual ideas made by hand and a graphic medium. Our impulse to make marks is evident in the long history of image making dating back to the earliest pictographs and petroglyphs to be found drawn and carved onto natural surfaces using little more than pigment and rock.

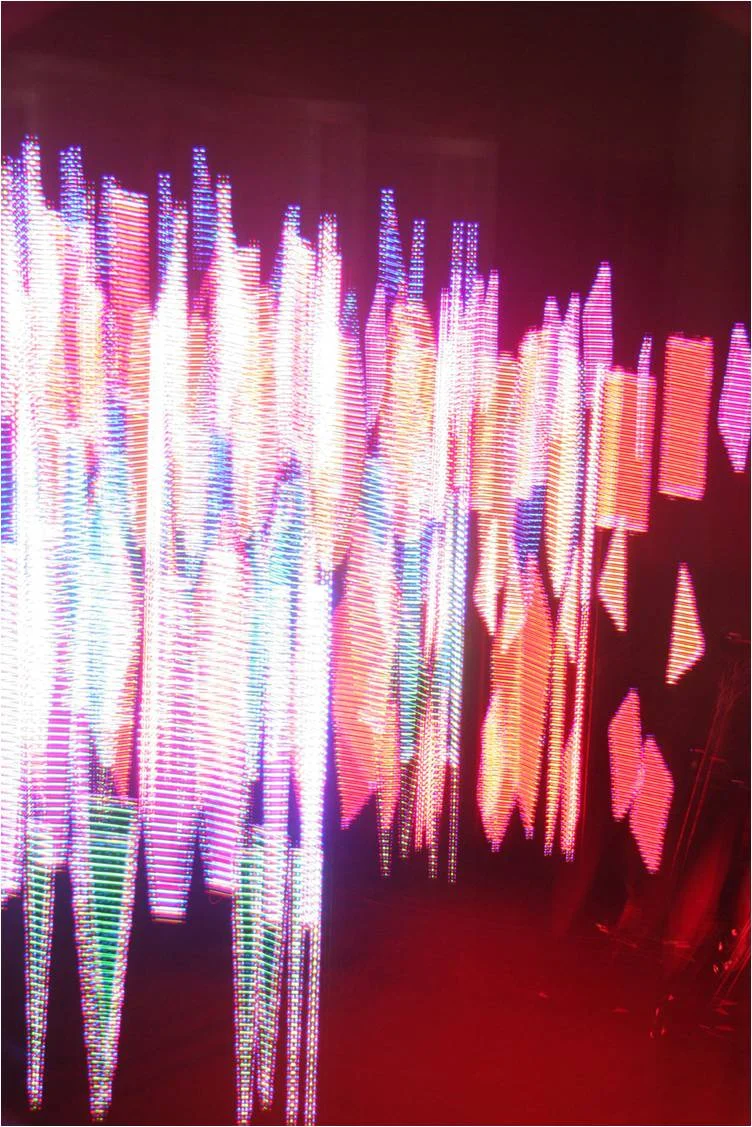

Fig.11 - Interactive RPT Wall Installation Nathan Cohen Ars Electronica Linz 2008

As part of my research, in seeking to invent spatially beyond a conventional pictorial format, I have been developing the integration of digital content in artworks incorporating interactive Retro-reflective Projection Technology and real time/time delayed video installations. By constructing the artwork in particular ways it is also possible to integrate digital content so that it does not appear to be constrained by the fixed framing format of a screen edge.

Fig.12 - Interactive RPT Wall Installation Nathan Cohen Ars Electronica Linz 2008: reflecting projected light

To find a form of visual expression that relates to the way we see encompassing a panoramic view and at a scale which encourages a more immersive and interactive experience is an intriguing proposition. When combined with the possibility of incorporating moving imagery the inventive potential is further developed. Enabling the image seen to be interacted with directly by the viewer, even locating their presence within the image itself in real time, confers a further layer of reading and interpretation and this is a process that I have achieved with the use of computing and video technology.

Fig.13 - Interactive RPT Wall Installation Ars Electronica: setting up video projection

A large scale interactive artwork was created for Ars Electronica which incorporated 3 layers of reading. The artwork spanned 5 metres across a wall and was composed of an irregular structure of light-reflective and painted panels which could be observed as an artwork in itself, with spatial ambiguity inherent in the construction's design, which while completely flat appeared quite 3- dimensional when observed from a distance. A second layer of reading was created by observing the artwork through a projector that revealed the supporting grid like structure of the image construction reflected by the retro-reflective panels incorporated into the artwork's construction. A third layer was then subsequently observed when a person moved between the projector and the artwork triggering a second projection incorporating a video sequence revealed in real time by their silhouette to a person observing through the projector.

Fig.14 - Interactive RPT Wall Installation Nathan Cohen Ars Electronica Linz 2008: first video projection layer seen through projector

Fig.15 - Interactive RPT Wall Installation Nathan Cohen Ars Electronica Linz 2008: figure moving in front of installation triggering second video projection layer as seen through projector

The original intention had been to create a live feed video stream for the second projection layer of what could be observed on the other side of the wall, so rendering this part of the construction transparent and the supporting wall invisible bringing the real world view into the illusion of space that is the artwork. The viewer would be interacting with an image that is simultaneously internal and external, a mirror of light and reflection and a window onto the world being observed.

The projection process has to be constructed with a computer programmed to drive the video sequences/live video feed and modifying the projections in relation to the sensor input, although the viewer will not necessarily be aware of this as the computer is not visible as part of the display. The results are engaging and stimulated considerable response on the part of viewers who interacted with the video projection and realized that in the viewing of the artwork they were active participants in the experiences of others who were also observing over time. This occurred in two ways; viewing through the projector as others walked up to and around the artwork, and being observed by others when approaching closer to the artwork.

The physical properties of the RPT reflective material offer a natural extension to the media familiar to the painter and allow for pictorial invention at a human and architectural scale. It can be cut into different shapes, applied directly to and bent around surfaces of different size and when viewed in ambient light conditions the light and dark grey of the RPT materials provide a tonal contrast that creates a balanced scale between black and white. Being highly light reflective when a more focused light is projected onto their surfaces the tonal scales shift, with the brightest element becoming the lightest of the grey RPT materials and the white non-RPT material surface seeming grey by comparison. This offers another means of playing with perception of space and depth within the artworks’ construction and can alter the illusion of the three dimensionality of the image given varying light conditions and projection.

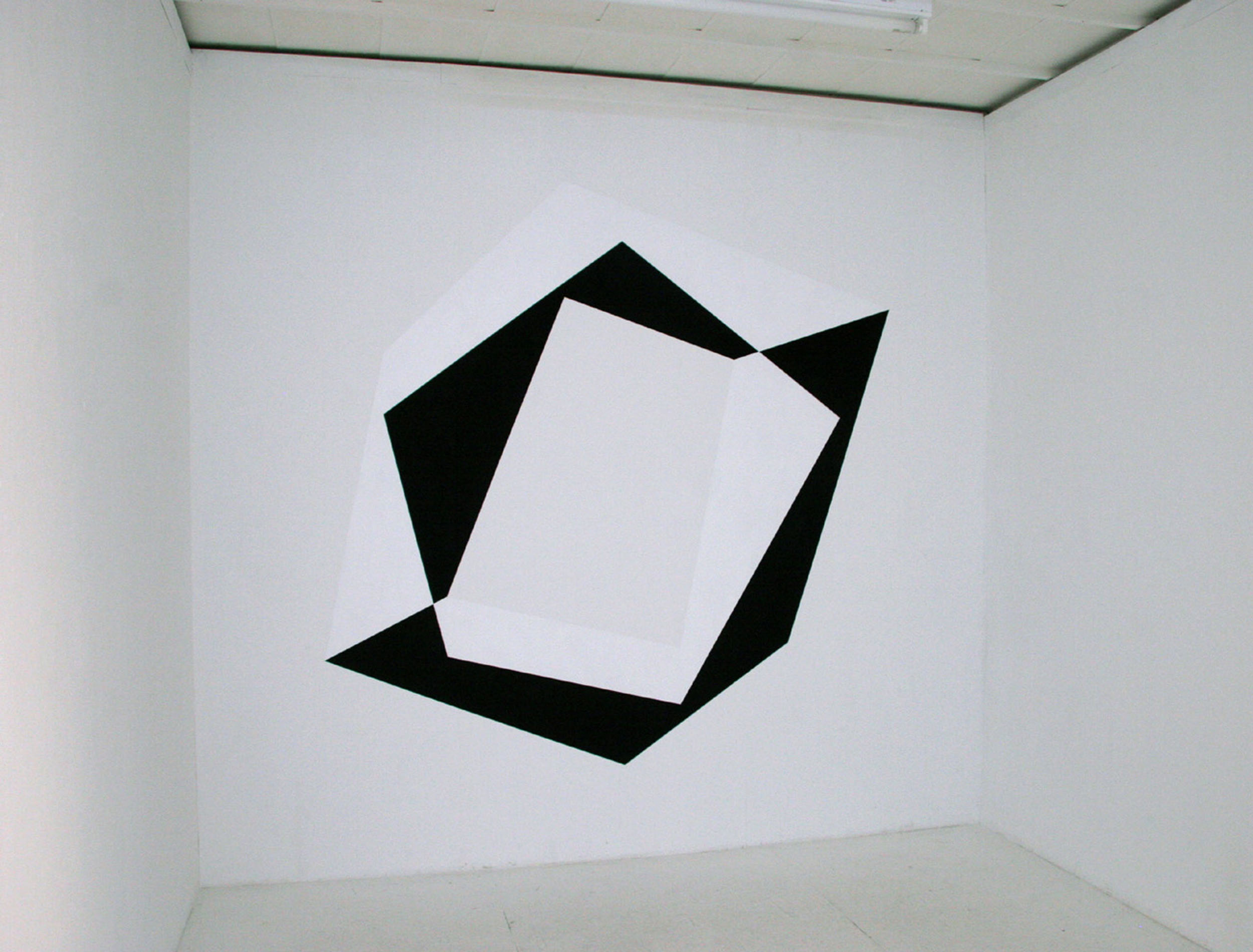

Fig.16 - Wall Installation Nathan Cohen Aisho Miura Gallery Tokyo 2009

In seeking to invent in my own work with images that appear three dimensional while retaining pictorial form (i.e. they are flat) and that have irregular boundaries I have created structures which are not confined to a picture window illusion of space. As the image also exists within the ‘real’ space of the viewer it becomes more architectonic in its spatial implications and activates a dynamic relationship with the ‘real’ space within which it exists.

When conceived on a human scale this allows for the creation of an immersive environment encouraging interaction with the artwork. When pictorial forms are combined in such a way as to challenge spatial interpretation a new dynamic unfolds resulting in images which are both intriguing and intellectually engaging. This can be developed overtly or subliminally, with the structure or physical construction of a work demanding visual dexterity in its comprehension while the light projected layering of imagery in selected elements offers multiple possibilities for spatial interpretation.

Fig.17 - Tokyo, aerial view

Tokyo provided the wider context for the exhibition Intangible Spaces at the Aisho Miura gallery (2010). The city is a complex and contrasting environment where the new rubs shoulders with the old; buildings constructed using the latest technology can be seen alongside centuries old shrines and temples which are examples of the technological innovations of their day. In the art installations I created for this exhibition I wished to capture something of the essence of this experience, with the gallery itself once being a house used by the local temple, now converted into a modern gallery space. The imagery used in the wall projections combined two recorded views of scenes observed in Tokyo at the time of the show: for the wall projections I contrasted video sequences of Tokyo panoramas viewed by day from the top of a high building, enabling the complexity of the city to be viewed from an unusual perspective, with the summer hanabi fireworks displays, momentary bursts of structured light seen at night.

Fig.18 - 'Intangible Spaces': setting up the projections

For the floor projection the technique originally conceived for the Ars Electronica installation was implemented, with the viewer observing a live feed video of what could be seen directly through the floor to the entrance of the gallery, so also linking the upper and lower spaces of the gallery in real time and developing the theme of the observer emerging into and being within the space at the same time.

Fig.19 - 'Intangible Spaces' installation view Nathan Cohen Aisho Miura Arts Tokyo 2010

The artworks included both wall and floor based RPT constructions that required interaction on the part of the viewer to fully observe their pictorial potential, for while the installation could be viewed as images that interacted with the architecture of the gallery space to create the illusion of three dimensional structures, when the projections were also seen through the RPT projectors an alternative reading of the space within the artworks was enabled. The intention was also to challenge pictorial convention in the way the artworks were located in space, utilizing the corner of the room and floor, locations not usually associated with the display of pictorial images.

Fig.20 - 'Intangible Spaces' installation view Nathan Cohen Aisho Miura Arts Tokyo 2010: wall and floor installations with projections

Fig.21 - 'Intangible Spaces' installation view Nathan Cohen Aisho Miura Arts Tokyo 2010: floor projection showing live video of view as would be seen though floor

We are familiar with looking into an imaginary space, and developments in immersive technologies have sought to place the viewer in ever closer proximity to the action. A third artwork displayed in the Tokyo exhibition develops the idea of locating the viewer within the space of the artwork itself and utilizes an approach to visual invention which could only be achieved using the computer.

Fig.22 - 'Intangible Spaces' Nathan Cohen Tokyo projectors and interactive video set up

As the visitor to the exhibition climbed the stairs to the installation located on the second floor their progress was being recorded by a small video camera. A short time lapse of the resulting video image was combined with isolating the visitor’s image from the background and a moving video sequence I had made of the art installation itself. The result was a video projection, which the visitor could view as they reached the top of the stairs, of themselves ‘climbing into’ and located within the artwork they would not yet have seen. This formed the start of the interactive process of viewing the art installations.

Fig.23 - 'Intangible Spaces' installation view Nathan Cohen Aisho Miura Arts Tokyo 2010: projected video feed image ascending stairs into installation

Memory forms an important part in our interaction with the world around us. There are many ways in which this can be explored and artists have sought to create images and art forms that rely for their interpretation upon experiences we have gained prior to their viewing. I am interested in creating artworks that encourage the viewer to be an active participant in the experience of encountering what they see. In this artwork this relies on a technological application that combines a small time shift and its projection into the moment of engagement – the person climbing the stairs encounters themselves in this act as they arrive at the point of viewing the artwork for the first time, and this marks the initial moment of engagement with the exhibition.

The seemingly mundane process of walking up some stairs can be represented to the viewer in a form that is not conventional, but relies for its interpretation on understanding certain conventions relating to how we interpret what we see. The context for this plays a part in how we choose to interpret what is unfolding before us, and the viewing of the artwork in the specific space and context of the other artworks that are also displayed in this video sequence requires the viewer to engage with the totality of the experience to be able to comprehend what is seen. This is a process that unfolds over the time it takes to view all the artworks in the exhibition, and rewards a return to the initial video sequence as, having seen the exhibition, the viewer can now understand the context for the imagery they initially see themselves ascending into in the time delayed video sequence.

The interactive nature of computer technology combined with the limitation of the flat screen encourages us to layer our experiences, moving from one window to another often displayed simultaneously.

Fig.24 - 'Where Am Eye' Nathan Cohen: test sequence

In considering how pictorial form can express different types of interaction with space it is necessary to look at the relationship of edge to surface, for the picture plane is often clearly defined by boundaries which separate it from the non-pictorial space of its surroundings, particularly on a more intimate scale such as a computer monitor or TV screen.

It is also important to think about how we perceive moving images; the saccade sequences of moments in movement neurologically processed giving the sense that these are contiguous over time. Then there is also the question of focus and angle of vision to be considered – how close or distant we are from what we see, and how we are located in relation to an action or object of interest and how this might alter our understanding of it. Light conditions also vary our perception of space.

In contrast to the larger more architectural interactive installations I have also been experimenting with animated sequences of recorded video images that are combined and composed over time and are formally articulated on the computer screen in ways that shift how we perceive them spatially and inform our memory of the actions that occur.

Fig.25 - 'Meal' test edit sequence Nathan Cohen 2012

Recent test pieces introduce fragmented and multi-faceted views of video sequences of human actions, such as walking through a space or cooking a meal. The shifting composition of these facets is intended to create a dynamic tension between the formal elements that compose an image and the edge of the space proscribed by the screen. With several views of the same activity displayed simultaneously within animated facets that shift over time it is possible to impart a sense of how it might feel to be engaging in the activity being viewed and to see this from multiple perspectives enhancing a sense of depth and movement within the picture plane of the screen and creating a more immediate presence of the activity. To this end I have found that by liberating the pictorial elements that compose this constantly changing sequence of images from the rectilinearly defined edges of the screen space it is possible to create a more dynamic sense of space, time, movement and association.

To create these art forms it has also been necessary to develop a close working relationship with experts in the field of virtual reality. Tachi Lab, a Tokyo based laboratory researching Telexistence directed by Professor Susumu Tachi, has developed technology to support research into ‘optical camouflage’ and ‘augmented reality’ and I have worked with this team in the development of new visual forms that can also be applied at an architectural scale. This is an ongoing and mutually beneficial relationship that has enabled me to create art work using novel technologies that have been adapted and developed beyond the use for which they were originally conceived as a result of this collaboration.

Fig.26 - Tachi Lab 'Intangible Spaces' planning meeting 2010

By extension, the process of inventing new ways to generate interactive digital images affords scope for researchers in the virtual reality field to develop their ideas beyond the utilitarian or functional in terms of application and might offer insight into the potential for this media to extend our perceptual capabilities as this technology becomes increasingly present and embedded within our everyday lives.

Fig.27 - Drawing for RPT Wall Installation Nathan Cohen 2008

When making choices about how to construct an artwork there are questions we may ask about how to build pictorially and spatially in ways that translate a deeper understanding of how we observe and perceive, and which in turn can be comprehensible to those who view what is created.

Neuroscience, and in particular the new discipline of neuroaesthetics 'whose goal is to find the neural basis of mental processes precisely related to art' seeks in part to explain abstraction as a function of the brains structure. As we learn more about the way in which different parts of the brain process stimuli so, perhaps, we shall gain a deeper understanding of why we see and invent the forms we create.

Fig.28 - 'Rainbow' Galisteo, New Mexico

It remains to be seen to what extent our ability to envisage the poetics of space, the landscape of the imagination and the creative intellectual processes that generate art can be accounted for by an analysis of our brain structure and its functions, but it is significant that this has in recent years attracted the interest of scientists.

Artists are constantly pushing the limits of the technologies and materials they work with often resulting in new and challenging forms and contributing to the adaptation and development of these media. This is an experimental process which can be unpredictable but also throws up the possibility for invention and the advancement of methods and processes that encourages collaboration between artists, technologists and scientists.

We are now living in an age where digital media offers for an artist another medium for visual invention, and in my utilization of computer articulated images in these artworks I am doing so with the purpose of enabling and enhancing perception. However, while exploring the potential new technologies have to offer in the conception and construction of an artwork I am also working with pictorial form that has a long history in its evolution, and in the process seeking new ways to construct pictorially that challenge our preconceptions of space. There is great scope for invention with all media and I endeavour to explore the potential for expressing ideas and experience in forms that utilize a range of techniques and materials. The digital forms one part of this process and is applicable when required to advance particular ideas I wish to explore.

Fig.29 - Nathan Cohen 'Pueblo - Santa Clara' 2014

I am interested in how experiences of the world can be translated through visual and abstract processes resulting in forms that do not rely for their interpretation on a likeness of things seen and yet can still convey meaning. Recent painted constructions explore memories of journeys through landscapes, encounters with artefacts, structures both natural and human made, architecture and visual forms that have inspired me as I seek a deeper understanding of what it is to exist and interact with the world around us.

Isaac Newton's observation relating to seeing further by standing on the shoulders of giants is also relevant to the artist as we seek to discover new insights made real through the art we make but also build upon the work of those who have preceded us in engaging with this challenge, a process embracing diverse sources of visual inspiration and intellectual enquiry. Consequently, the history of our quest is a rich one which is global, cultural and shared by artists across generations.

Fig.30 - Silbury Hill

That we are capable of inventing with a means of expression that can translate ideas and insights, embrace new thinking and approaches to visualizing what we see and encounter and articulate this in ways that enable engagement by others in this experience, is a creative and challenging prospect. As an artist I interpret the nature of what I see through the artworks that I make and in the process seek to encourage others to see the world afresh and perhaps in new and different ways.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

- Illuminating Thought; Imaging Reality Nathan Cohen, Berkeley 2003

- 'Art, we shall find, is inseparably related to [our] growing faculty to visualize and reason about [ourselves] and [our] environment in an ever more accurate manner.'

Art as the Evolution of Visual Knowledge Charles Biederman, Red Wing, USA 1948 - 'Just as the grammar of music consists of harmony, counterpoint, and form which describes the structure of a composition, so spatial structures, whether crystalline, architectural, or choreographic, have their grammar which consists of such parameters as symmetry, proportion, connectivity, stability, etc. Space is not a passive vacuum; it has properties which constrain as well as enhance the structures which inhabit it.' Connections; The Geometric Bridge between Art and Science Arthur Loeb, Chemical Physicist, quoted by Jay Kappraff, World Scientific 1990

- 'The abstract tendency has led to the magnificent systematic theories of Algebraic Geometry, or Riemannian Geometry, and of Topology; these theories make extensive use of abstract reasoning and symbolic calculation... Notwithstanding this it is still true today that intuitive understanding plays a major role in geometry' and 'With the aid of visual imagination we can illuminate the manifold facts and problems..

'Geometry and the Imagination S. Cohn-Vossen, David Hilbert, Chelsea Publication 1952 - Digital da Vinci; Chapter 4 Brain, Technology and Creativity. Brain Art. R Folgieri, C Lucchiari, M Granato, D Grechi, ed. Newton Lee Springer 2014

† Nathan Cohen - about the author:

As an artist I am interested in how we see the world around us and how this can be altered through images and physical interaction with space and visual form. I have been exhibiting internationally for 30 years, including solo shows at Annely Juda Fine Art London; Museum Mondriaanhuis (retrospective) Holland; Tokyo Gallery Japan and many other venues worldwide.

My interdisciplinary research in art and science embraces neurobiology, optics, virtual and augmented reality technologies which has resulted in interactive art installations exhibited at Ars Electronica Austria, the Aisho Miura Gallery Japan and University College London. I seek new ways to develop and extend our understanding of what we see and how we interact with our environment and in collaboration with researchers in Japan and the UK I have been creating artworks that challenge our spatial perception, incorporating motion sensing and real-time projection into 2 and 3-dimensional constructions created to give the impression of a multi-layered space.

In addition to my work as an artist I set up the MA Art and Science at University of the Arts London (CSM) in 2011. Over the years I have found that there is a deep interest in exploring areas of creative and intellectual enquiry that do not necessarily fit into single subject areas and encourages the investigation of ideas that may be shared across disciplines. By creating an environment that encourages this we can be most inquisitive and allow ourselves the opportunity to challenge preconceptions as we discover new connections and evolve different strategies for advancing research and creative practice.

I have, in addition to my studio practice, been engaged in publishing, directing an archive, curating exhibitions internationally and writing.